In Form 3 (grades 7-8,) a new Natural History assignment appeared on the PNEU programmes. While in Forms 1 and 2 students were simply told to “Keep a nature notebook,” now in Form 3, they were instructed to keep a “Nature Notebook with flower, bird and insect lists, & make daily notes.”

“The Lists” as they were commonly referred to, were described by G. M. Bernau in this way:

The children should also keep a flower list, i.e., a diary of when each flower has been first seen in the year; a tree list, saying when each tree comes into leaf and flower; a bird list, stating when a bird is first seen, etc. (PR 4, p. 605)

Some students also kept lists of mosses, lichens, fossils, animals, and birds’ nesting dates, such as “the dates when the song was first heard, nest building began, eggs were laid and hatched, nestlings took flight.” (Drury, PR 24, p. 188)

Each list item included the common name of the specimen and also the scientific name. Alfred Thornley, an examiner of the House of Education student-teacher nature notebooks, exclaimed in his 1926 yearly report: “The searching out of the scientific names is a good discipline which helps to promote more exact observations, and to systematise them. Let us have scientific names please!” (PR 37, p. 137) Agnes Drury, Natural History teacher for the House of Education, explained further, that the use of Latin names shows the relationship between species where English names cannot.

English fails to tell us that stitchwort, chickweed and starwort all belong to one genus. … Unless we are familiar with them, we may miss the connection between insects and the plants they feed on which is often recorded in their names. It is true we have in English such names as the privet and poplar hawk moth, the cabbage white butterfly, and the chalk-hill blue. But the similarity between the scientific names of butterfly and flower is commoner still. For example, the caterpillar of the small tortoiseshell, Vanessa urticce, feeds on the stinging-nettle, Urtica dioica. And that of the Cinnabarmoth, Hipocrita jacobcea, feeds on ragwort, Senecio Jacobcea. (PR 24, p. 188)

In the early years of list keeping, examiners reported that the largest number of wildflowers found in one month was just under 200 flowers. In later years, when the students’ notebooks were being reviewed only once a year, reports were often made of students who had logged 300 – 500 wildflowers and 70 – 90 birds in the year! Imagine the effort students would have put in daily to listen and look for birds, and to search every corner for a new flower in bloom, noting what they had seen last year at this time as a hint of what to look for on this day. M. L. Hodgson, the House of Education natural history teacher, said, “It is very interesting to go for a walk with the avowed intention of seeing how many plants can be found out in flower, to write the list in the note-book, and to compare lists made year by year, or month by month.” (PR 4, p. 69)

The comparisons of these lists offered much to the students’ education. Drury explained how vast and varied these comparisons could be:

They enable one to compare one year with another, e.g., the day the ryegrass flowered, or certain dragon flies emerged ; to compare one county with another, for example, a mountainous with an agricultural region, or a limestone flora with that of a slate country ; to compare one month with another, showing for instance, that the daffodil has a very short season and the chickweed blossoms month after month, or which flowers open in June, which in July, and so on. They distinguish the resident from the migratory birds, and show whether the latter return or leave at about the same date. (PR 24, p. 188)

Today many scientific organizations seek the help of citizen scientists to collect information from their local area in order to track the migration of birds or note the spread of a non-native species of plants, among other things. It is also a means of noting changes to climate, both now and in Charlotte Mason’s day:

Many excellent lists of flowers for April and May have reached me this year, both from students and pupils. In Ambleside we had several lists of 127 plants seen in flower between April 17th and April 30th. Those of you who have lists for the corresponding dates of last year will understand how very different our weather has been this year. (Hodgson, PR 7, p. 315. Emphasis mine.)

I have personally enjoyed contributing to the websites eBird, where I work hard to accurately identify the species’ for which I am providing data. (Recently the look of a hawk I was trying to identify was so similar to another hawk that I couldn’t confidently identify it until I had compared the calls of each. I may not have made the effort if not for the perceived accountability.) In School Education, Charlotte Mason explained why the power to recognize and name for classification is important:

In Science, or rather, nature study, we attach great importance to recognition, believing that the power to recognise and name a plant or stone or constellation involves classification and includes a good deal of knowledge. To know a plant by its gesture and habitat, its time and its way of flowering and fruiting; a bird by its flight and song and its times of coming and going; to know when, year after year, you may come upon the redstart and the pied fly-catcher, means a good deal of interested observation, and of; at any rate, the material for science. (p. 236)

I think this is one of the primary reasons the lists were not assigned until Form 3. Before that Charlotte Mason talked about students making rough classifications, which enhance their ability to observe and discern between very similar species. This foundation prepares them well for later searching in a field guide to identify flowers and birds they have seen while out in the field. How often have you opened a field guide to identify a bird you thought you had looked at very carefully only to find that there are three or four very similar birds to choose from? Maybe you didn’t think to look for an eye ring or the color of its beak? It’s happened to me a number of times. In her article, “The Charm of Nature Study,” G. Downton reinforces this idea:

The power to classify, discriminate, and distinguish between things that differ is amongst the highest faculties of human intellect, and no opportunity to cultivate it should be allowed to pass. For this reason children should be encouraged to make such rough classifications as they can with their slight knowledge of both plant and animal forms of life. (PR 42, p. 188)

In Home Education, Charlotte Mason referred to “Calendars,” or what is sometimes called “A Book of First.”

“It is a capital plan for the children to keep a calendar––the first oak-leaf, the first tadpole, the first cowslip, the first catkin, the first ripe blackberries, where seen, and when. The next year they will know when and where to look out for their favourites, and will, every year, be in a condition to add new observations. Think of the zest and interest, the object, which such a practice will give to daily walks and little excursions.” (p. 54)

As Home Education presents the foundation of Charlotte Mason’s philosophy and curriculum and is therefore primarily focused on children younger than Form 3, when the lists were first assigned on the programmes, I think we can confidently think of these calendars as something a family or school can contribute to. Indeed, the House of Education had a school list that was added to by the residents over the course of many years.

The lists assigned to students in Form 3 and beyond, however, were to be personal lists, kept in their own nature notebooks. Early on, they were scattered throughout the book on a month by month basis, but later they were relocated to the back of the book. In the Parents’ Review article “Nature Work at the House of Education,” H. D. Geldart described the change:

They were in this form useless for comparison, without a great deal of reference to and fro. They are now kept in a tabular form, showing at a glance the work of the whole term or even of the whole year.” (PR 9, p. 488-89)

In “The Charm of Nature Study” Downton described their organization:

“These lists work best kept in columns, with the name, number, and date of finding all on one line, and the next underneath and so on. Latin names, and names of families are a great help in classification and Latin names for flowers are invaluable, especially in cases where a single flower has a different name in practically every county.” (PR 42, p. 188)

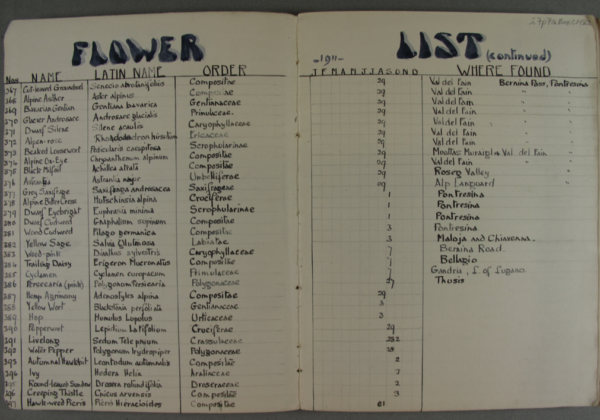

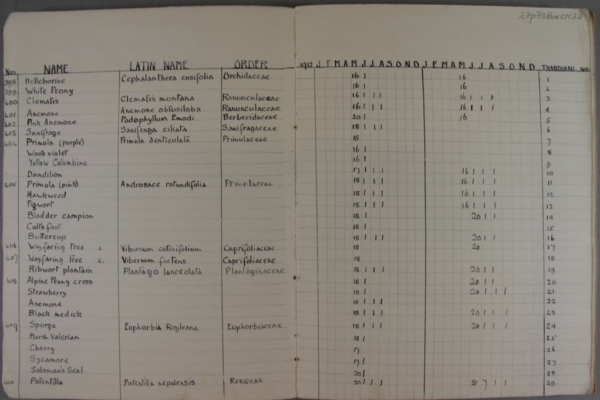

An example of a flower or bird list may look as follow:

No. | Common Name | Scientific Name |Family | Where Found |J|F|M|A|M|J|J|A|S|O|N|D|

For instance, suppose we first see daffodils in bloom for the first time on February 13 — we would write the common name, the scientific name, and the family across the row. We would also make a note about where we saw them. Then in the column for February (F) we would write 13. If we saw that the daffodils were still in bloom in March, we would go to the same row and add an X in the column for March (M.) (See examples below.)

A separate list should be kept for each item: birds, flowers, insects, and any other species a student wished to track, and of course, plenty of space should be left in case the hunt that year turns up hundreds of species!

Keeping a list while traveling seems to be a useful occupation as well. Lists of birds and plants could be compared to those seen in your home region, and lists of shells, fossils, or other items not seen at home, would be a valuable collection.

The Lists were considered in the yearly review of student-teacher notebooks, and the critiques often included notes such as, “carefully done,” “well prepared,” “full,” “incomplete,” “short,” “be more careful about scientific names.” It was clear that the challenge was very attractive to some students. Downton pointed out that the “practical child who loves organising, will enjoy planning out lists of the different things that are to be kept in the book.” (PR 42, p. 187)

Below are two pages of Margaret Deck’s flower lists. In Thornley’s “Report Upon the Nature Note Books”, he listed Miss. Deck first in Class I, with the critique: “Deck, Margaret. The drawings in this book are of great excellence. The notes are nice and full, and the Lists are good.” (PR 23, p. 227-28) (You may click on the images below to view them larger.)

Source: Archive.org, Charlotte Mason Digital Collection, Margaret Deck, 1910b.

I only began keeping lists six months ago, but already they have become something of an obsession. I will admit, however, that I have chosen to tweak them just a bit by moving them to a separate notebook. Students at the House of Education generally filled one notebook per year starting in January. To compare their lists they would only need to look back at last year’s nature notebook. I hope to continue this practice for many years, however, and therefore, I chose to purchase a Blueline Business Notebook which is hardcover and has graph paper inside.

I will also share that correction tape has been an essential help to me. If you click on the above image and look closely, you will see that I use it a lot! Sometimes I write in a name that I later find is incorrect or I misspell something. I try not to be hard on myself about it because I think I’m learning a lot. I don’t need to be perfect; I just need to be doing it.

Eventually, Drury succeeded Thonely as the examiner and in her “Report on the Twenty-Two Nature Note Books of 1941” she commented: “I have paid great attention to the lists, for they are of more value than anyone can realise unless she keeps one faithfully.” (PR 53, p. 59) I hope this will inspire you to start some lists of your own so you can learn for yourself what she means.

Eventually, Drury succeeded Thonely as the examiner and in her “Report on the Twenty-Two Nature Note Books of 1941” she commented: “I have paid great attention to the lists, for they are of more value than anyone can realise unless she keeps one faithfully.” (PR 53, p. 59) I hope this will inspire you to start some lists of your own so you can learn for yourself what she means.

References:

Deck, Margaret. “Two Nature Notebooks by Margaret Deck (1910 and 1912). ARMITT Box ALM127, File CMC519, Items 1-2.” WorldCat, www.worldcat.org/title/nature-notebooks-by-margaret-deck-1910-and-1912/oclc/932129030&referer=brief_results.

Geldart, H. “Nature Work at the House of Education.”Parents’ Review, vol. 9, 1897, pp. 487-495.

Bernau, G. M. “Children’s Museums.” Parents’ Review, vol. 4, 1893, pp. 603-605.

Downton, G. “The Charm of Nature Study.” Parents’ Review, vol. 42, 1931, pp. 184-190.

Drury, Agnes C. “Nature Study.” Parents’ Review, vol. 24, 1913, pp. 187-190.

Drury, Agnes C. “Our Work.” Parents’ Review, vol. 53, 1942, p0. 59-60.

Hodgson, M. L. “Notes By The Way.” Parents’ Review, vol. 4, 1893, pp. 68-70.

Hodgson, M. L. “Our Work.” Parents’ Review, vol. 7, 1896, p. 314-315.

Mason, Charlotte M. Home Education, 1886.

Mason, Charlotte M. School Education, 1904.

Rankin, Florence. “Notebooks from Eve Anderson, Including 2 Nature Notebooks (by Florence Rankin 1894 & 1899), Book of Centuries, by Eve Anderson, and History of Education, by Eve Anderson. ARMITT Box PNEU24, File pneu162, Items i1(a)p1pneu162-i5p142pneu162.” WorldCat, www.worldcat.org/title/notebooks-from-eve-anderson-including-2-nature-notebooks-by-florence-rankin-1894-1899-book-of-centuries-by-eve-anderson-and-history-of-education-by-eve-anderson-1894-1952/oclc/931544866&referer=brief_results.

Thornley, Alfred. “Our Work.” Parents’ Review, vol. 23, 1912, p. 227-228.

Thornley, Alfred. “Our Work.” Parents’ Review, vol. 37, 1926, p. 136-137.

These nature lists remind me of the Book of Firsts. Would it be necessary to keep nature notebooks/lists and a “firsts” notebook? Just curious about your thoughts on the subject. I’m trying to avoid starting, then stopping numerous notebooks because of so much overlap. But, if there are specific helpful reasons to do more of them, I’m up for the task.

Hello, Becca. These lists were not started until Form 3 (grades 7-8.) Before that, only a nature notebook is required. I do talk about Calendars or Family Diaries or what we sometimes hear called the Book of First in the article The Golden Hours. Reading that might help you see the difference. I think the main thing to focus on is the nature notebook. Then when a child is old enough and has spent ample time studying nature, adding the lists will be the natural next step. ~Nicole

Thanks for sharing this link.

Nicole,

I noticed you added tabs to your notebook. That’s a great way to stay organized. How many pages do you leave available before adding another tab for a different kind of list?

Hello, Mariana. I just divided the book up randomly, making sure there were lots of pages between each tab. ~Nicole

Should we recommend a certain minimum of entries for a child who needs accountability (per term or year) or is that too restrictive? I have a son who is er in need of such support sometimes in his endeavors.

Hi, Heather. I think it would be better to do it as a family or even you and he do it together rather than forcing entries. Keeping lists is hard and takes real dedication. I think having a partner would help a lot. Just a thought. ~Nicole

Would like to recommend the printable book of firsts that Celeste on joyouslessons.blogspot.com

They make a nice easy start for list keepers. I’ll be printing several copies for my form 3 students this year, or having them keep it as a group.