In Home Education, Charlotte Mason referred to nature notebooks as nature journals. What is being recorded, however, is not a daily record of a person’s life, but a narration of the beauties God has revealed to us. For a journal of any kind to be useful, the entries must be descriptive enough to give a sense of what the writer has seen, heard, tasted, touched, and smelled. It’s not surprising then, that one of the most common negative critiques of the House of Education student-teachers’ notebooks was a general lack of description:

Hussey, A. A. … There are too many vague and loose statements. (PR 27, p. 156)

Alfred Thornley explained: “Now and again the observations recorded are a little superficial, and sometimes words are too vaguely used, and sentences do not always convey a clear idea of what was really seen.” (PR 21, p. 228)

In the same way, Agnes Drury emphasized the importance of accuracy:

The interest in birds is remarkable, but there are few notes to enable the writer to recognise her bird a year later. Accuracy should be the aim as opposed to vagueness. For example, notes on dragonflies, with one exception, give no indication of the size, or even relative sizes. Generalisations about weather, harvest, fall of leaves, or differences between Ambleside and the South, if vague, are useless; but by exact statements evidence is accumulated. (PR 52, p. 62, emphasis mine)

In her article, “How to Keep a Nature Note-book,” Drury gives an example from her own book. Notice the level of detail seen in this record:

September 1st. Just after the sun had set, I saw the hummingbird hawk-moth feeding on red spur valerian. The proboscis was so long that less than half of it seemed to me concealed by the flower. The antennae were long and conspicuous, and the wings moved so fast that I could only see the orange colour of the hind-wings. So I should suppose the fore-wings moved faster. The end of the abdomen was black and white. It was a little moth for a hawk-moth. Later, resting on a wall, it was quite inconspicuous. (PR 52, p. 226-27)

Elsewhere Drury praises students for recording measurements: “Notes of the time taken by the capsule of Pellia to burst and scatter its spores show an awakened interest. There are quite a number of notes that estimate size, distance and quantity.” (PR 56, p. 54)

What interests me is the amount of practice this kind of recording may require. When I take a walk, I often see many notable items, but remembering all of the details upon my return can be challenging. This can be compared to the effortful task of narration, but instead of reading a chapter in a history book, for example, we are reading a chapter in nature. Rather than remembering a list of kings and his contemporaries, we are trying to remember a list of plants, animals and insects, and such details as their estimated size, where we found them, and what was growing nearby. Thornley commented on this challenge when one of his walks with the House of Education student-teachers was poorly narrated:

By way of adverse criticism, I must say that in too many books there is a looseness and vagueness of expression which is a little trying. This is especially the case in the reports upon my walks with the Students. This is probably due to some extent to the large number of new objects forced upon our attention owing to the zeal and energy of the Students : and can probably be remedied by shortening our walk a little and increasing our talk in the Schoolroom afterwards. (PR 27 p. 156)

We must remember though that when the weather cooperated, Thornley spent one or two entire days in the fields with the students so we cannot use this is an excuse to take shorter afternoon walks. Nevertheless, it is valuable to recognize that to accurately narrate a nature walk takes some work and will require practice.

Another thing to keep in mind is that we don’t have to narrate every last thing we have seen. Often in Drury’s notebook, a single account was recorded. For instance, once she mentioned standing on a bridge when a bird surprised her by flying out from under it. She described several details about the encounter, including the bird’s flight pattern, coloring, and size. (PR 41, p. 193) It was a good sized entry, but that is all she mentioned that day. She was an avid observer, so she likely saw more than just the one bird, but she honed in on that one thing. Elsewhere she clarified, “Each one records in her own Nature Note Book that which has interested her…” (PR 34, p. 370)

Another aspect that may require practice is learning to describe what we have seen without it sounding like a monotonous list. Thornley once commented, “I notice a tendency on the part of a few students to present their notes rather too much in the form of a ‘catalogue ‘ than as a chronicle of living interest.” (PR 45, p. 135) Florence Rankin’s first notebook is a good example. During her first few months at the House of Education, her nature notes were somewhat stilted:

April 8. Found the garlic in bud. Ash in full flower.

But after a few months her notes began to be more descriptive and eloquent, reflecting greater confidence:

Oct 1. At Ambleside again. The country looks lovely in its autumn aspect. In the morning it is very cold and misty – almost foggy – later on the sun bursts out and makes everything warm and mellow. Fairfield Basin is more beautiful than ever. Many flowers are still in bloom here that have finished flowering in Essex : honeysuckle, stitchwort the lesser, goldenrod, water dropwort, broomlime, money wort…

The latter example is so much more enjoyable to read, giving a much fuller picture of the scene. Also, while the writer seemed to value accuracy, only the October entry gives us a sense of her interest and joy. The most highly ranked books always accompanied praise for this quality. Thornely reported:

Fourteen of [the books] keep up well the fine standard of work that one always looks for in everything that comes from Scale How. They are permeated with a real love of Nature. In them is portrayed, by word…, something of the wonder, and the beauty, and the power seen in the world of living things by which we are surrounded. (PR 26, p. 234)

Vince, H. F. A very nice book indeed. … many of the notes of great interest.

Purves, G. M. An excellent book : full of interest. …

Walker, F. A most industrious Student. The book is full of good notes …

Fletcher, V. A good book, with … interesting notes. (PR 27 p. 156)

You may wish to reflect on the notes you have made in your nature notebook. Do they display a good balance between accuracy and a love for the subject? Have you written clear descriptions of what you have observed but also expressed your appreciation for “the wonder, and the beauty, and the power seen in the world of living things”?

Source: Archive.org, Charlotte Mason Digital Collection, Margaret Hickling, 1934-36.

When To Make Notebook Entries

The goal of a nature walk looks different when we take our nature notebooks into the field. Instead of going out with the intention of finding many items of interest, big or small, simple or complicated, solid as a rock or more of an idea or a question; we go with the goal of finding something to paint — something that we feel capable of painting, something that will fit on a page in our notebook. Unfortunately, this causes our focus to narrow, and instead of coming home with a robust list of things to write about in our nature journals, we have spent a great deal of time focused on one thing.

Waiting a few hours or until the next day to make a nature notebook entry would not have been unusual for Charlotte Mason’s students. I see many comments from Thornely and Drury that indicate students wrote about their excursions or daily walks when they returned home or to the classroom. In Thornley’s article “Nature Study in the Home” he described the importance of having a definite aim for a nature walk, after which he said: “Then on the next occasion when lessons are resumed the note-book must be brought out, and the children encouraged to make some notes, or little drawings of what they have seen.” (PR 19, p. 726)

He got that idea from Charlotte Mason, who in a letter drafted to Thornley several years earlier, explained that there was a set time for House of Education students-teachers to make entries in their nature notebooks:

Half an hour a week in the actual time table time [is] given for the entry of the nature notes & the illustration but most students I think give a few minutes a day to entering notes of what they have seen in that days walk or perhaps painting some objects (the illustrations once a student gets into the way of it can be done in a surprisingly short time). (p. 4)

In her article “The Approach to Nature Study,” Downton even clarified that there was time set aside in the children’s schedule as well: “Special time is allowed on the time-tables of all the forms in the Parents’ Union Schools, but this is only a foundation, as one might say, for a child can, and is encouraged to, paint and write notes at any time.” (PR 47, p. 338)

The sample time tables available in the archives do not indicate a specific time to make nature notebook entries as part of the morning schedule, and homeschoolers will likely find it is best done as part of the afternoon occupations. But if your family needs some accountability, these references should give you the confidence to add it in your morning schedule for a term or for a year to create a habit or otherwise get some momentum.

We see many examples in the student-teachers notebooks of entries made after a delay. There were times when multiple outings were added at once. For instance, in Margaret Deck’s book we see a single entry accounting for two walks taken on the same day:

August 6th. This morning as we were going through a large wood, we saw a snake gliding … This afternoon we went a long walk and found any amount of flowers, … (emphasis mine)

Even in Drury’s student-teacher notebook, we see the following entries:

March 10th. Yesterday morning we saw the first lambs, four of them. They are very small but sturdy with their stout-looking woolly legs, rather weak at the knees.

In the evening after rain, I smelt the fragrance in the air for the first time this year. It was chiefly from the pines in the churchyard.

The rooks are busy building their nests. One I noticed to-day carrying a big forked twig which took up far more space than he did, for all his broad wings.February 26th. Yesterday was a foggy day, and just before one o’clock I heard my first curlew whistle, just one and no more. To-day, being out at 8.30 a.m. for half-term holiday, I saw a flight of ducks or wild geese. … A lovely night followed the happy day and I saw Arcturus rise before I went to bed : one of my signs of on-coming spring!

March 16th. From Sunday, 11th, to Thursday, 15th, we had five sunny days and consequently found coltsfoot out, opposite-leaved golden saxifrage (but not the alternate), pistillate hazel and alder, staminate willow, and wych elm. I went up Great Langdale yesterday … (PR 41, p. 190, 196-197, emphasis mine)

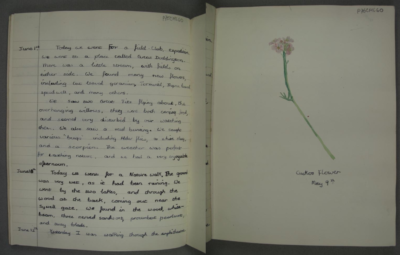

There are also examples in Margaret Hickling’s notebook, a student of a public Parents’ Union School. The following example would have been made three days after the walk was taken as July 6, 1936, was a Monday. Notice the amount of detail she was able to include:

July 6. Last Friday we went for a Nature Walk. We went past the works to the ice-house plantation. We saw lots of dragon flies over the lake, and in the water we found a dead grass-snake over two feet long. On a tree stump we found a very large slug. We picked it up on a twig, it hung from it by means of the excretion from its salvier gland and produced enough to reach the ground without falling. We crossed the stream near the filter-house and made our way to the main path, the undergrowth is very thick, especially the nettles. We came back past the tree stump to see if we could find the slug to take back with us, but though we found several traces of its trail there was no sign of the slug itself.

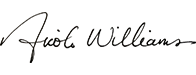

In the student-teacher notebooks, periodically we see that a drawing was made and dated, and then the previous two or three days worth of entries were written around the illustration. A similar thing happened to me recently. During my walk, I collected a specimen to paint, but then I couldn’t decide what to do first, paint or write my notes. In the end, I paint the flower first because it was fading fast. But when I was done, I realized that I hadn’t made any notes about my walk from the day before, so I wrote those notes first and then I added the current day’s notes. It worked out fine, and I was happy to include a record from both days.

It’s important to recognize, however, that waiting too long to make an entry is not the ideal for any of us because as I said before, to accurately narrate a walk takes some effort. Drury warned, “Dated notes have a permanent value which becomes greater with every year added, provided the notes are written at the time, not some time later when the impression has faded.” (PR 52, p. 220)

You can see how valuable the notes are when recording a pageant of the seasons. As students of Charlotte Mason, we daily read living words and practice expressing ourselves clearly, descriptively, and with a sense of beauty. What better subject is there for us to hone these skills than describing the natural world we have inherited. As Charlotte Mason said, in the first book of Ourselves:

There are few joys in life greater and more constant than our joy in Beauty, though it is almost impossible to put into words what Beauty consists in; colour, form, proportion, harmony––these are some of its elements. Words give some idea of these things, and therefore some idea of Beauty, and that is why it is only through our Beauty Sense that we can take full pleasure in Literature. But Beauty is everywhere — in white clouds against the blue, in the grey bole of the beech, the play of a kitten, the lovely flight and beautiful colouring of birds, in the hills and the valleys and the streams, in the wind-flower and the blossom of the broom. What we call Nature is all Beauty and delight, and the person who watches Nature closely and knows her well, like the poet Wordsworth, for example, has his Beauty Sense always active, always bringing him joy. (p. 41-42)

Resources:

See the article Notes, part 1 for suggested supplies (including notebooks and paints.)

Image Source: Archive.org, Charlotte Mason Digital Collection, Florence Rankin, 1894.

References:

Deck, Margaret. “Two Nature Notebooks by Margaret Deck (1910 and 1912) ARMITT Box ALM127, File CMC519, Items 1-2.” Internet Archive, Charlotte Mason Digital Collection, 1910, archive.org/details/BoxAML127FileCMC519.

Downton, M. G. “The Approach to Nature Study.” Parents’ Review, vol. 47, 1936, pp. 333-339.

Drury, Agnes C. “From a Nature Notebook” Parents’ Review, vol. 41, 1933, pp. 188-197.

Drury, Agnes C. “Our Work” Parents’ Review, vol. 52, 1941, pp. 62-63.

Drury, Agnes C. “How to Keep a Nature Note-Book” Parents’ Review, vol. 52, 1941, pp. 218-233.

Drury, Agnes C. “Our Work.” Parents’ Review, vol. 56, 1945, p. 54.

Geldart, H. “Nature Work at the House of Education.” Parents’ Review, vol. 9, 1897, pp. 487-495.

Hickling, Margaret. “Nature Notebook by Margaret Hickling, Overstone [Northamptonshire] School Pupil 1934-1936 ARMITT Box CM8, File CMC60, Items p1cmc60-p122cmc60.” Internet Archive, Charlotte Mason Digital Collection, 1934, archive.org/details/BoxCM8FileCMC60icmc60.

Mason, Charlotte M. “Draft Letter from CM (in E. Kitching’s Handwriting) to Rev. Alfred Thornley Re Nature Diaries at the House of Education & 2 Letters from Rev. Alfred Thornley to Charlotte Mason on His Examination of Nature Diaries [Nature Notebooks] 1901-1903 Box PNEU2A, File pneu11 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive, Charlotte Mason Digital Collection, 1901, archive.org/details/PNEU2AFilepneu11/page/n1.

Openshaw, May. “House of Education Student’s Nature Note Book, by May Openshaw, Scale How 1912 ARMITT Box CM24, File CMC175.” Internet Archive, Charlotte Mason Digital Collection, 1912, archive.org/details/BoxCM23FileCMC159i1-7_201608.

Rankin, Florence. “Notebooks from Eve Anderson, Including 2 Nature Notebooks (by Florence Rankin 1894 & 1899), Book of Centuries, by Eve Anderson, and History of Education, by Eve Anderson. 1894-1952 [?] ARMITT Box PNEU24, File pneu162, Items i1(a)p1pneu162-i5p142pneu162.” Internet Archive, Charlotte Mason Digital Collection, 1894, archive.org/details/BoxPNEU24i1Ap1-i1Dpneu162.

Thornley, Alfred. “Nature Study in the Home.” Parents’ Review, vol. 19, 1908, pp. 721-729

Thornley, Alfred. “Our Work.” Parents’ Review, vol. 21, 1910, pp. 228-229

Thornley, Alfred. “Our Work.” Parents’ Review, vol. 26, 1915, pp. 234-235.

Thornley, Alfred. “Our Work.” Parents’ Review, vol. 27, 1916, pp. 155-156.

Thornley, Alfred. “Our Work.” Parents’ Review, vol. 45, 1934, p. 135.

[…] (← last article | next article →) […]