I’ve had several opportunities over the last few years to lead workshops about Charlotte Mason’s method of science. Incredibly, there is so much to cover that even when I am given several hours and a particular topic or age range to focus on, I still find myself rushing because I know I cannot cover everything in time! Also, I know that there are so many of you who have not had the opportunity to attend a Charlotte Mason conference or retreat. Therefore, I have prepared an organized series of articles to share with you, starting with the nature work that begins before school and continuing through formal science.

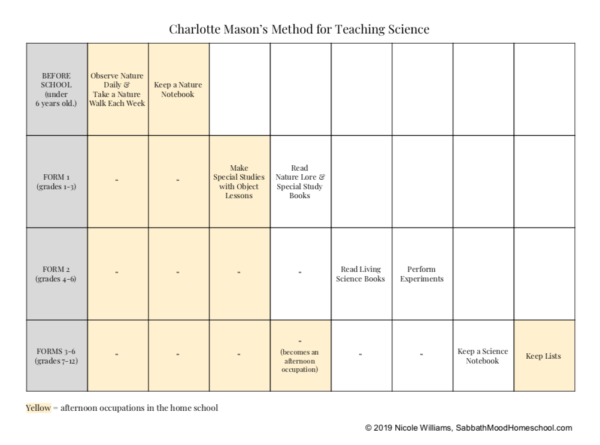

Below is a chart that I created to show the progression of science within the Charlotte Mason method. Note that I’ve used the ditto mark (”) to indicate that an activity is continued in the next form. For instance, Special Studies are begun in Form 1 but are continued throughout all of the following forms. In fact, that is the theme of this chart — the idea that once an activity is begun, it continues throughout the student’s education. This is helpful information if you begin using Charlotte Mason’s method in a later form, because it may be necessary to spend a term giving some extra attention to the earlier forms before settling into the form that is appropriate for your child’s age. I also hope you will notice that we are building a foundation for science in the lower forms — a very necessary foundation.

Click this link to open a printable version of the above chart.

In this series, we will look at each of these components, but today let’s start with the big picture.

Charlotte Mason described her model of education as a method rather than a system, and she said a method implies two things — 1) “a mental image of the end or object to be arrived at,” (that is the big picture, or the long term goal,) and 2) “a step by step progress in that way,” (that is the day to day work.) (vol. 1, p. 8)

I believe that we have to buy into the end that Charlotte Mason presents to us, or we won’t be faithful to the step by step progress. For many parents, the end or object to be arrived at is passing achievement tests, graduation, college, and a career, and Charlotte Mason does assure us that doing science this way will prepare our students for these things. But the real reason she thought we should do science using her methods is that we have a responsibility to prepare our children to have a full life. Have you ever heard the Charlotte Mason quote about setting our children’s feet in a large room? Well, Charlotte Mason was talking about science in that quote:

We prefer that they should never say they have learned botany or conchology, geology or astronomy. The question is not,––how much does the youth know? when he has finished his education––but how much does he care? and about how many orders of things does he care? In fact, how large is the room in which he finds his feet set? and, therefore, how full is the life he has before him? (vol. 3, p. 170)

When we make the goal of education merely the mastery of subjects, we all lose. Miss Mason said, “Where science does not teach a child to wonder and admire it has perhaps no educative value.” (vol. 6, p. 224) That means that the goal of school science cannot be to prepare students for a possible career in a scientific field or an examination to show proficiency, but instead that they come to feel something for the natural world they live in and make strong connections to it. Mason explains this by comparing our world to a family estate, in which a child feels a connection to its heirlooms:

Geology, mineralogy, physical geography, botany, natural history, biology, astronomy––the whole circle of the sciences is, as it were, set with gates ajar in order that a child may go forth furnished, not with scientific knowledge, but with, what Huxley calls, common information, so that he may feel for objects on the earth and in the heavens the sort of proprietary interest which the son of an old house has in its heirlooms. (vol. 3, p. 79)

But what is the common information that she refers to? We often use the word common to describe something at its base level — maybe even less than par. But what Charlotte Mason was talking about is what we call scientific literacy today. She quoted Sir Richard Gregory as he explained what that entails:

The essential mission of school science was to prepare pupils for civilised citizenship by revealing to them something of the beauty and the power of the world in which they lived, as well as introducing them to the methods by which the boundaries of natural knowledge had been extended. School science, therefore, was not intended to prepare for vocations, but to equip pupils for life. It should be part of a general education, unspecialised, in no direct connexion with possible university courses to follow. (vol. 6, p. 222)

Robert Hazen and James Trefil talk about scientific literacy in the preface of their book Science Matters:

It is not the specialized stuff of the experts, but the more general, less precise knowledge used in political discourse. If you can understand the news of the day as it relates to science, if you can take articles with headlines about stem cell research and the greenhouse effect and put them in a meaningful context—in short, if you can treat news about science in the same way that you treat everything else that comes over your horizon, then as far as we are concerned you are scientifically literate. (p. xii)

Charlotte Mason’s goals for school science were to instill a sense of wonder and awe in students and provide them with the common information that allows for scientific literacy. The former will enrich their lives, but the latter is a lofty goal. It means more than preparing a student for college entrance exams and possible university courses to follow. It also means building them up to be citizens who can think, form opinions, discuss, and vote on the scientific issues of the day.

If we have the conviction to embrace these as our long term goals, then we can confidently settle into the day to day steps — we can follow the method. We can shut out the noise of fear, look at the child across from us, and use Charlotte Mason’s methods to work through today’s assignment. It’s in this way that we daily treat our child as a born person, and prepare him “to take his place in the world at his best.” (vol. 1, p. 9)

Join me over the next several months as we look at each part of Charlotte Mason’s method for science. It may not be at all similar to what you experienced during your school days, but as with every aspect of Miss Mason’s approach, you will find it very natural to the children.

Further Resources:

Science As The Last Hold Out

Science Matters by Hazen and Trefil — On Amazon use the “Look inside” to read the introduction.

Science: A Vast & Joyous Realm — Teacher Training Video by me on A Delectable Education

References:

Hazen, Robert M., and James Trefil. Science Matters: Achieving Scientific Literacy. Anchor Books, 2009.

Mason, Charlotte M. Home Education, Vol. 1, 1886.

Mason, Charlotte M. School Education, Vol. 3, 1904.

Mason, Charlotte M. A Philosophy of Education, Vol. 6, 1925.

Nicole, this is just spot-on and full of truth! Thank you for being a rock in regards to science in a CM education. This is the one area that I most struggle with and have to continually talk myself off the cliff edge because I’m not using the “rigorous” textbooks that most others use….even many CM educators! Your article was the truth and clarity that I needed to reaffirm my beliefs in this method and to stay true to the principles and walk by faith. Thank you for your amazing ministry and service to the CM community.

-Laura

Thank you, Laura. I have an article prepared for this series comparing living books to science books. I think it might cure you for good. 😀 I hope this series helps many people see the whole scope of Charlotte Mason’s science and feel the confidence they need. Thank you for the encouragement. ~Nicole

Nicole, I’m so encouraged by what you read and write. Your teacher training video Science: A Vast & Joyous Realm was so insightful. Thank you for all your time you put into helping others.

Thank you for your kind words, Karen. They are an encouragement to me.

~Nicole

Is there an age/form when the children should start reading the books themselves and do written narration in their science notebook with just over-sight from the parent? My son will be in form 3 next year and I purchased a few lesson plans from you. It looks like he might easily do them by himself and then just share what he is learning with me via his notebook and I watch his experiments? Is that taking a step too far away?

Thank you for this amazing website and the podcast. They have both been so helpful!

Hello, Samantha. Form 3 is the appropriate time to start keeping a science notebook with written narrations in it. And you are correct that most Form 3 and above students should be able to do the work with just over-sight from the parent. In fact, I write my Form 3 and up guides to the student. (Some need more involvement from an adult or older student, but that is for the parent to decide.) I think you are on the right track.

~Nicole

[…] to How to Do Nature Study (← last article | next article […]